Painting The Flow, Color and Rhythm Of Water

Jan 04, 2005

"Painting The Flow, Color and Rhythm of Water" by William H. Hays

published in American Artist Magazine, April, 2005

Surely one of the most beautiful and entrancing elements of most landscape scenes is light passing through and reflecting on water. Whether addressing the sea, a lake or a stream, water presents one of the most challenging aspects for any landscape painter to master. I have made the different moods of water and important part of my landscape painting for more than 30 years. For me, there are three basic elements I consider when painting water: color, rhythm and flow.

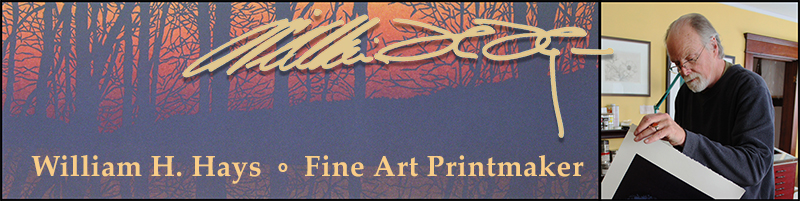

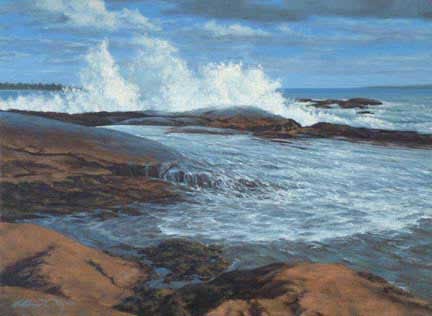

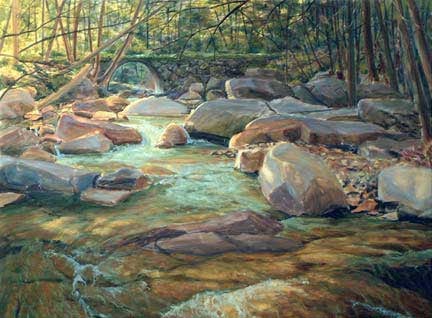

"Carters Beach Rocks" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

"Carters Beach Rocks" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

Let's start with flow. Water is constantly moving from the influence of wind, wave action and its own flow responding to gravity. Streams and rivers flow subject to the terrain over which they course. I try to envision what is below the water's surface from the beginning stages of the painting. Deep water generally flows slower with a smoother surface, its reflections a gentle repeating sweep grabbing the colors of the sky and of the immediate surroundings. Shallow areas ripple and course their way over stones, sand and debris on the bottom. The result is a more complex swirling of broken reflections - curling dashes and slashing strokes of paint.

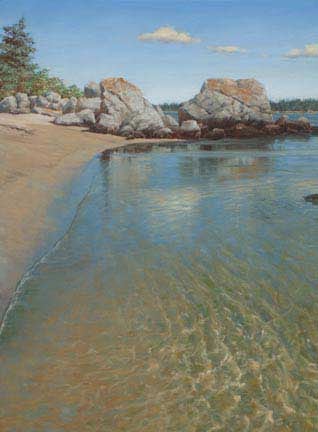

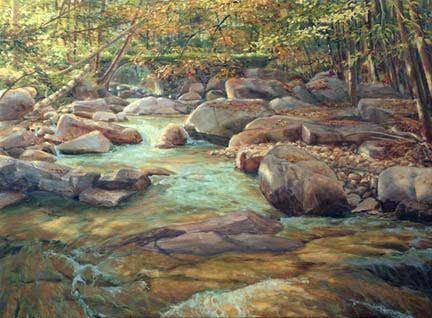

"Pikes Falls" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

"Pikes Falls" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

Throughout the painting I try to feel and understand the flow of a stream or river from the bottom up. What happens below the surface creates the reflective qualities of the surface and the refractive qualities of the water itself. Which brings us to color.

Working from the bottom up, the depth of the water creates its own color. In nature water is almost never pure and therefore tends to a greener tint of the cerulean and cobalt blue of pure water in quantity. The color of the water is subject to the light of the day and the type of water. A clear overhead light creates a dominant blue in clean water that I usually approach with ultramarine blue combined with other notes. The clear north Atlantic Ocean is quite (ultramarine) blue and rather dark.

A lake, river or stream generally tends more toward green. Particles suspended in the water reflect more light, creating an overall lighter tone in fresh and shallow water. As depth increases the value of the blue-green decreases, it gets darker. In shallows the bottom gathers the higher and warmer notes of the palette. Yellows, oranges and reds figure more prominently with sunlit and shallow areas, raising the values to the higher range within highlights. This is all within the water, not on the surface.

On the surface, shadow areas from objects immediately adjacent to the water tend not to reflect the object, but rather offer a window to under the surface. This is generally due to the object blocking the reflection of the sky. The reflection of the sky dancing on the surface is mostly a deeper version of what is seen in the sky itself. For the sake of this discussion, let us assume it is a clear, blue-sky day. In choosing a color for the sky reflections, the value of the blue must be at least a shade darker than the sky itself and should be more intense and at least a little lighter than the dominant values in the water.

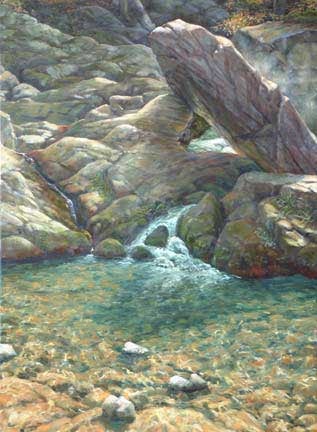

"Red Boat with Lobster Pots" oil on panel 11" x 24"

"Red Boat with Lobster Pots" oil on panel 11" x 24"

The value contrasts between the water and reflection are the central element that describes the reflection as light bouncing off of the surface. This means that while painting the water you need to keep in mind what is yet to come, the reflection of the sky and sun. The reflected light is usually much lighter than refracted light within the water. For sky reflections I will often choose a mix of ultramarine blue and cobalt blue - an exquisite combination with maximum intensity. It is the reflections of the sky that define the rhythms of the surface.

"Beach Meadows I" oil on canvas 28" x 38"

"Beach Meadows I" oil on canvas 28" x 38"

Rhythm and regimentation are the goal and the pitfall, respectively. It is rhythm in brush strokes that adds texture and motion to the composition. The rhythms of blades of grass in the field are a common example of rhythm vs. regimentation for most students. A quick, thin stroke will define a blade of grass. The repetition of that stroke will define a field. But if the brush strokes are done the same way again and again, the repetition becomes regimentation that takes the life out of the painting. Repeated strokes become pattern rather than rhythm. The trick is to find the descriptive stroke and then repeat it differently each time to create interest within the rhythm rather than killing it with sameness. In working with the surface of water, the rhythms can range from simple and elegant to very complicated and multi-layered. In all cases these rhythms reflect and define the flow of the water. A calm day in deep water produces undulations that I often approach with a dry brush technique. I push around the shadows and highlights so that they flow into one another and gently take the viewer's eye back into the composition.

"Sunset Mooring" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

"Sunset Mooring" oil on canvas 38" x 28"

In water that ripples and flows over obstacles the reflection is broken up. The rippling surface picks up much less of the sky reflection. The sky and reflections of objects define the surface motion with what might be simply a matter of selected notes.

I like to approach this type of reflection with a filbert or flat that is at least twice the size I would naturally choose. One can turn or rock the brush while drawing the brush across the surface and let the edges and the end of the brush do the work for you. Don't get caught up in details. Let the brush strokes happen with confidence and look for what they can accomplish without getting caught up in specifics. Then step back and let the painting tell you what is working then build on it.

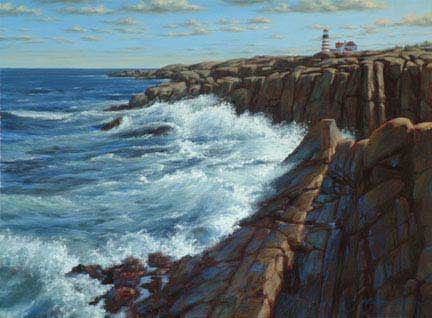

"Standing Up To The Sea" oil on canvas 28" x 38"

"Standing Up To The Sea" oil on canvas 28" x 38"

Given the important role that the surface reflections play (defining the flow and physical depth), it is important to not overwork them. Approach the addition of reflected light strokes with economy. By frequently stepping back and noting the effect of these strokes, you can minimize their use while maximizing their effect.

The relative success of landscapes that include water as a major element of the composition are dependent on a lively portrayal of that water. Lack of contrasts or lack of interesting use of color in the water can cause the most beautifully rendered surroundings to fall flat. By looking below the surface of water while painting, the depth of the scene is strengthened by including this constantly moving and rich space. The viewer is taken below the surface with you. The undulations of flow, reflection and refraction provide the artist with a rich composition tool that embraces viewers and leads them through your painting.

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step by Step

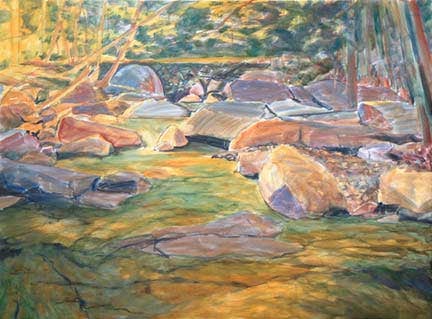

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step One

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step One

The composition is blocked in according to light and shadow areas of the painting. Sunlit areas begin with a thin under painting of yellow ochre while shadow areas begin with cobalt blue mixed with raw umber. Notes of terra rosa carry reflected light into the shadow areas. The bottom of the stream bed is tinted with cerulean blue, permanent green and raw umber. Terra rosa tints the brighter shadows in the water. The dark fissures and ledges on the stream bed are laid out with irregular strokes created with a flat brush that is twisted and turned while being drawn across the canvas. The artist is working very fast without paying much attention to particulars. The water flowing over the stream bed breaks up any structures below the surface.

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Two

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Two

The overall tonal qualities are taking shape between light and shadow. Shadow areas in the rocks are fleshed out with warm and cool darks using primarily terra rosa and an ultramarine and cobalt blue mixture. The gray violets add life to the warm underpainting in the shadows on the rocks and pull in the color of the sky to be added later. Terra rosa and yellow ochre add depth and warmth to the downward slopes of underwater rocks.

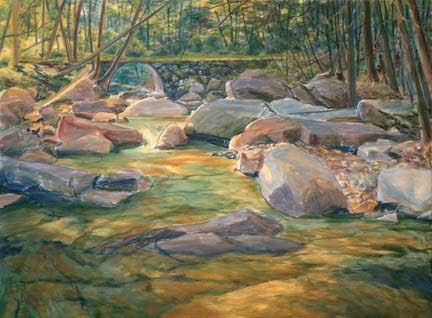

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Three

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Three

At this point I am still painting the bottom and under the surface of the water. The churning of air in the water and the overall flow are defined with a grayed down tint of cerulean blue and permanent green light. In shadow areas I use a blue version of the same tint for the "white" foam of the water. Underneath I continue to develop the shaded areas of stones with different tints of terra rosa and yellow ochre.

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Four

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Step Four

The addition of foliage in the trees rounds out the mood of painting while bringing the visual space closer to the viewer. The warmer colors and layering mid-ground and background colors focuses the depth of the painted space to the upper left center by bringing the upper right closer to the viewer. The colors of the foliage are brought down onto the ground litter, unifying the scene.

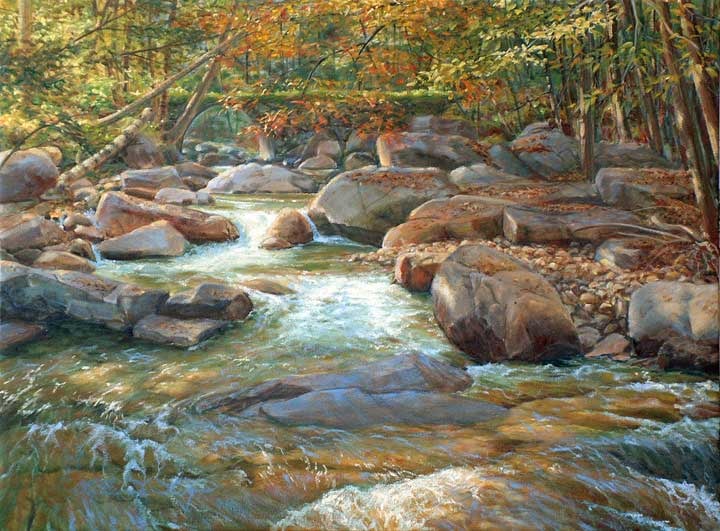

"Stickneybrook Bridge" Oil on Canvas 28" x 38" by William H. Hays

Finally, surface reflections are composed of a tint of yellow ochre for the brightest highlights. Churning, white water in shadow is a gray blue. The reflections of the sky are a mix of ultramarine and cobalt blue dragged over the surface quickly, in discreet strokes that follow the flow of the water. The addition of these combined highlights focuses the composition and describes the water as having depth.

I hope you've enjoyed this example of my painting techniques. Feel free to write, I enjoy hearing from you!

Copyright 2004, William H. Hays