Thinking about prints

Dec 25, 2010

Prints… You see the word all the time. At one time, a print was a marvelous innovation in public art that allowed almost anyone to own a work of art by an admired artist. The first European prints were woodcuts. They became quite popular with the advent of the printing press. Artists like the German, Albrecht Dürer got very good at the techniques and his carved wood blocks were used for many thousands of impressions. They were so durable that sometimes the blocks were used to make prints well beyond the death of the artist who carved the block.

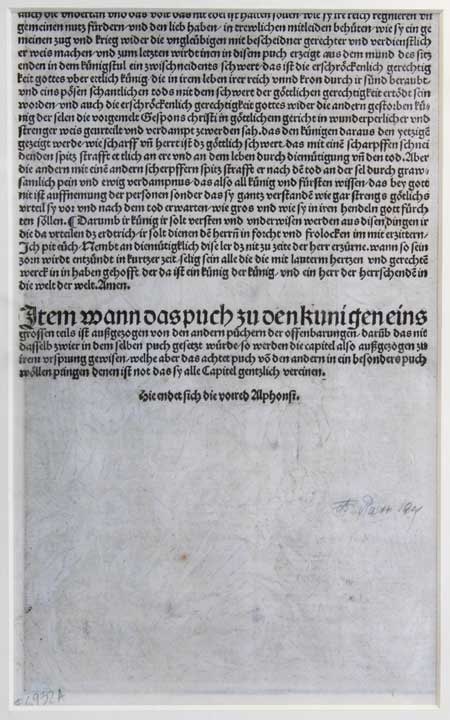

I have a woodcut print by Dürer that is the 16th image (of 16) from a book entitled, “Revelations of Saint Bridgette.” (Sometimes it is spelled Brigitta, Brigid, Birgitta or Bridget.) This particular print depicts Bridgette passing out copies of her revelations to the royalty and church leaders of Europe. Some are not receiving it well and they can be seen in the lower portions of the illustration in the fires of hell and the mouth of the demon (above).

She has an interesting story, this Saint Bridgette. She was born the daughter of a governor and wealthy land owner who was related to the king of Sweden in the early 1300s. She married, had children and periodically received visions of celestial beings from her childhood. In 1336 she received an extended series of intense visions and messages that she wrote down and sent off to the leaders of Europe and the Roman Catholic Church. The writings were pretty well ignored by the leaders and she was ridiculed by the church for her presumptions regarding how they should clean up their act and cease with the corruptions of the church and state.

In the 1340s, after a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella in Spain, her husband died. Her children were grown and she decided to devote her life to service and prayer. She moved to Rome in 1350 and established her own order of devotion with the blessings of the Pope. Although the establishment of the day did not look kindly on the revelatory admonitions Bridgette received, wrote down and distributed, the ordinary people of Europe were very receptive. She became a folk hero among the people.

Her vision of the nativity was perhaps the primary source for what we think of as the creche scenes and adoration scenes of art and popular culture from the Renaissance through today. Bridgette died in 1373. It was her received vision of Mary that began the popular idea that Mary was a blond woman. But most of her visions had to do with what constitutes righteous behavior and devotion to the will of God – for the people, but especially for the royal courts of Europe and the hierarchy of the Catholic church.

Though popular, her revelations were slow to be distributed since they had to be copied by hand, one sentence at a time. It was not until the 1440 (almost 70 years after her death) that the printing press with movable type was invented by Guttenberg.

In about 1500, somebody in Germany decided to publish a Latin edition of Bridgette’s revelations. Albrecht Dürer was a well-known artist at the time and he was enlisted to do 16 illustrations for the edition. It was a very popular publication and a second edition was published around 1503 in the German language rather than the original Latin. It is this second edition from which the print I own was taken. I’ve framed the print so that the back of it can be seen too. Below is the print, front and back.

I’ve followed the images with the text of the last paragraph of German. I’ve transcribed this as best I can. Remember, this is more than 500 years old, in German black script and a little difficult to read. My German is not good enough to translate this. Maybe someone could help out here?

“Item mann daspuch zu den kunigen eins grossen teils ist aussgezogen von den andern puchern der offenbarungen darub das nit dasselb zwier in dem selben puch gesetzt wurde so werden die capitel also aussgezogen zu frem vrspwng gewisen welhe aber das achtet puch vo den andern in ein befondere puch wollen pangen denen ist not das sy alle Capitel gentzlich vereinen.

Sie endetsich die voired Alphonsi.”